SOME ATTACKS ON THE TICK – From Pesticides to Guinea Hens!!!

This

is the program we have been running in Saltaire and Fair Harbor for the past

few years. and who are attempting to continue the program beyond the

experimental phase.

New

York Times Editorial Page

May

16, 2012

Ticks to the Slaughter

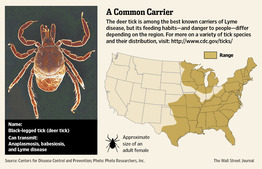

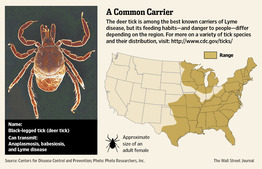

The mild winter is promising to bring a bad summer for disease-causing

parasites like the deer tick, which causes Lyme disease, a danger throughout

the Northeast. A three-year experiment in tick control in two areas of Long

Island — Shelter Island and western portions of Fire Island — has shown

encouraging results.

Researchers from Cornell University installed and monitored dozens of “four-poster”

feeding stations, which lure deer to a bin baited with corn and rigged with

rollers soaked with a tick-killing pesticide, permethrin. When a deer rubs

against the rollers, ticks die by the thousands. One station can treat all the

deer in about 100 acres.

New York had banned four-poster devices because feeding wild deer makes them

congregate, which increases the risk of spreading chronic wasting disease. The

Department of Environmental Conservation approved the experiment for these

confined areas, where Lyme infections were severe and chronic wasting disease

unknown.

The experiment was a departure for the cautious conservation department, and it

faced resistance from hunters who didn’t like the idea of permethrin in their

venison. But, under pressure from Shelter Island residents, the project was

approved. Hunters were assured that the pesticide, commonly used in shampoos

for head lice, showed up only on the skin and hair of affected deer, not in

muscle.

The results were excellent: Tick populations were reduced by more than 90

percent, according to the study’s report issued last year. Scientists are

cautious about predicting a comparable drop in Lyme disease because so many

factors are involved in its spread. But the experiment, which ended last year, seems

well worth continuing and expanding to other parts of Long Island.

Please dress appropriately when

you are working in your garden

This Season's Ticking Bomb

Warm Weather Means Ticks Will Be Out Early; A 'Horrific' Season for Lyme and

Other Diseases

By LAURA LANDRO

They

can wait for months, clinging to the edge of a blade of grass or a bush, for

the whiff of an animal's breath or vibration telling them a host approaches.

They

are ticks—and when they attach to your skin and feed on your blood over many

days, they can transmit diseases. Often hard to diagnose and tricky to treat,

tick-borne illnesses—led by Lyme disease—can cause symptoms ranging from

headache and muscle aches, to serious and long-term complications that affect

the brain, joints, heart, nerves and muscles. Preventing bites to head off

illness is particularly important, experts say, because the complex interaction

between ticks, their hosts, bacteria and habitats isn't completely understood.

Warmer

temperatures are leading some experts to warn that tick activity is starting

earlier than usual this year, putting more people at risk.

"This

is going to be a horrific season, especially for Lyme," says Leo J. Shea

III, a clinical assistant professor at the Rusk Institute of Rehabilitation

Medicine, part of New York University Langone Medical Center. He is also

president of the International Lyme and Associated Diseases Society.

Lyme

may be identified after a tick bite, for example, by an expanding rash that

looks like a bull's-eye. But that doesn't always happen, and even after a tick

bite, antibodies against Lyme may not show up for weeks, so early blood tests

can turn up false negatives. Symptoms such as fatigue, chills, fever, headache

and swollen lymph nodes may be misdiagnosed. Some infections can go undetected

for months or even years. When caught early, tick-borne diseases can be treated

successfully with two weeks of antibiotics, but doctors and researchers still

argue about whether a chronic form of Lyme exists, and whether it should be

treated with longer courses of the drugs.

Around

the country, state and federal health officials are battling a continued rise

in tick-borne diseases including Lyme, babeosis, and Rocky Mountain spotted

fever.

Between

1992 and 2010, reported cases of Lyme doubled, to nearly 23,000, and there were

another 7,600 probable cases in 2010, according to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. But CDC officials say the true incidence of Lyme may be

three times higher. Other infections, including babesiosis, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and anaplasmosis are steadily increasing, too. While not all

ticks carry disease, some may spread two or three types of infections in a

single bite.

Researchers

say the primary reasons for the global rise of tick-borne illness include the

movement of people into areas where animal hosts and tick populations are

abundant, and growth in the population of animals that carry ticks, including

deer, squirrels and mice.

"We

haven't even begun to scratch the surface of the type of pathogens ticks can be

harboring and transmitting," says Kristy K. Bradley, state epidemiologist

and public health veterinarian for the Oklahoma State Department of Health.

Animals

"are a traveling tick parade," Dr. Bradley adds, with pet dogs

"bringing them into the home and onto furniture and carpets."

The

brown dog tick, pictured, can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

Regularly

checking the body for ticks can reduce exposure, because removing them quickly

can prevent transmission of disease, says Kirby C. Stafford III, chief entomologist

at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, or CAES, in New Haven.

Showering

or bathing quickly after being outdoors can also help wash off crawling ticks

or make it easier to find them. What won't work: simply jumping in the pool or

lake, because ticks can hide in bathing suits and don't quickly drown in water.

There are tick-repellent sprays for clothes, but it is wise to immediately

launder and dry garments at high temperatures after hiking or golfing in areas

where ticks are present.

The

CDC is conducting the first study of its kind to determine whether spraying the

yard for ticks can not only kill pests, but also reduce human disease.

Participating households agreed to be randomly assigned a single spray with a

common pesticide, bifenthrin, or one that contained water, without knowing

which they would receive.

Paul

Mead, chief of epidemiology and surveillance activity at CDC's

bacterial-illness branch, says preliminary results from about 1,500 households

indicate that a spray reduced the tick population by 60%.

"But

there was far less of a reduction in tick encounters and illness,"

indicating that even a sharp drop in tick populations leaves infected ones

behind. "We may have to completely wipe out ticks to get an effect on

human illness," he says. The CDC is enrolling

households for a second arm of the study and expects final results late in

the fall. Organic repellents such as Alaska cedar are also being tested in

other studies.

Sometimes fire is the only solution: Wildlife biologist Scott C. Williams roams

Connecticut's woods armed with a propane torch to incinerate clumps of

Japanese barberry, an invasive plant species that chokes off native vegetation

and provides a favorite habitat for ticks.

The

CAES program to control the red-berried shrub—once cultivated as decorative—is

part of the growing, multifaceted effort around the country to prevent the

spread of infections like Lyme, which Mr. Williams has been treated for twice

since beginning the project in 2007.

Dr.

Bradley's home state of Oklahoma is one of several working with the One Health

Initiative, a global program to improve communication between physicians and

veterinarians to prevent the spread of infectious disease from animals to

people, such as recommending tick collars, sprays or topical treatments with

pesticides for dogs.

One

problem, says Laura Kahn, a founder of One Health, is that "vets don't

like to advise people on human health and physicians don't typically think

about these things, so it falls through the cracks." About 75% of new

diseases that have emerged globally in the last 30 years are spread from

animals to people, many of them through ticks, says Dr. Kahn, who is also a

science-and-global-security researcher at Princeton University.

Jason

Lipsett, 21 years old, was diagnosed with Lyme in November, after suffering for

three years with symptoms including problems with his jaw, recurring sinus

infections, migraines and trouble sleeping. He had to give up playing tennis

and take a medical leave from Bentley University in Waltham Mass., where he was

a senior. He doesn't remember being bitten by a tick but had been camping in

the woods in New Hampshire and often spent time outdoors during the summers at

a family home in Cape Cod.

Doctors

told him he might have chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia. Depressed

about his health, he began seeing a therapist who knew about the symptoms of

Lyme and referred him to another physician. That doctor determined he had

Lyme—and babesiosis, caused by a parasite that destroys red blood cells.

Mr.

Lipsett has been on an antibiotic regimen for four months. He says he has felt

better each month and that he is prepared to stay on the drugs until he and his

doctor are confident the disease is under control. He is making up courses and

hopes to graduate next year. He plans to participate in a 5K run on April 29 to

raise money for Time for Lyme, a Stamford, Conn. nonprofit that supports

research into Lyme and other tick-borne illnesses.

"I may not be able to

run, but I'm going to try to walk it," he says.

Hen-pecked

approach to Lyme disease

By MICHELLE CELARIER New York Post

Last Updated: 10:19 AM, July 13, 2012

It’s a hot summer in the Northeast — but not as hot as the quirky

little market for guinea hens, the latest fad for the monied set looking to do

battle against Lyme disease-carrying deer ticks.

These hens, with their patterned plumage and stark white faces,

are the latest backyard accessory dotting Hamptons estates and suburban horse

farms because of their voracious appetites for all things buggy, including the

dreaded deer tick.

Rob Schuster, whose Schuster’s Poultry Farm in Lakewood, NJ, has

sold a record 60 guinea hens this year — 10 times the number he sold all last

summer — and at times has had trouble keeping them in stock.

They cost about $8 per keet, or baby, and $25 or more for an

adult.

The bull market in guinea hens was sparked by talk that 2012 will

be a bad year for deer ticks. Dr. Richard Ostfeld, of the Cary Institute of

Ecosystem Studies, in Millbrook, Dutchess County, said a boom last year in the

population of tick-carrying white mice is behind the expected spike.

Oddly, supermodel Christie Brinkley is credited with starting the

guinea hen craze in 1990, after running an experiment on her Hamptons property

that found the birds eat a lot of deer ticks.

Read more: http://www.nypost.com/p/news/local/

hen_pecked_approach_to_lyme_disease_

M1RXhyqUjzOTBQaaBEfyCI#ixzz20tmVb7Ue

You can buy them - http://www.millroadhatchery.com/